Between Stone and Code

A conversation with artist and designer Carlo Vega on craft, technology, and human expression.

By Nando Costa on October, 2025

For many years, Carlo and I were working in the same field of animation, and yet it was only about seven years ago when we first met via a Microsoft project. Aside from his warm and calm demeanor, what struck me then was the way he talked about his work. He seemed to care more than most about the meaning behind every one of his design choices.

While nowadays Carlo and I work together on user experiences, it is his sculptures and other tactile works that I wanted to talk to him about, including his commitment to achieving his vision and innate curiosity to exploring ways to get it done. I hope you enjoy our conversation and find his work as interesting as I do.

How has growing up in Peru shape your artistic sensibility?

Growing up in Lima completely shaped my visual library. My family is originally from Ancash, in the Andes, and coming from modest means meant that people often made the things they needed or wanted.

I remember my grandmother knitting or sewing clothes for the family, or crafting toys for the children, and others writing letters with beautiful calligraphy. Those daily experiences taught me to see materials, colors, and techniques as part of normal daily life, and not something separate from it.

That sense of care, and resourcefulness in making has carried into how I approach my own work today.

Have you discovered ways in which your Peruvian heritage manifests in your work?

The day I became an artist was the day I left Peru when I was 11. My earliest works were purely digital, experimenting with software and techniques, chasing visuals that felt new or trendy. But over time, I stopped caring about the gesture of the visual itself and began focusing on what may exist beyond it.

For me, that often means memory: the distance from the land where I was born, the act of remembering something that may no longer exist. Out of those moments, a visual language emerges that is undeniably Latin American in its patterns, colors, and textures.

I often get materials made by artisans, like handmade paper or charcoal, even if I could buy a version in a store, because the origin of each piece matters. My goal isn’t to make work that looks Peruvian, but to make work that feels true to me. That translates into work that reflects the duality of my life between Peru and New York, between today’s tools and older crafts, between me and my ancestors.

That honesty is how my heritage manifests.

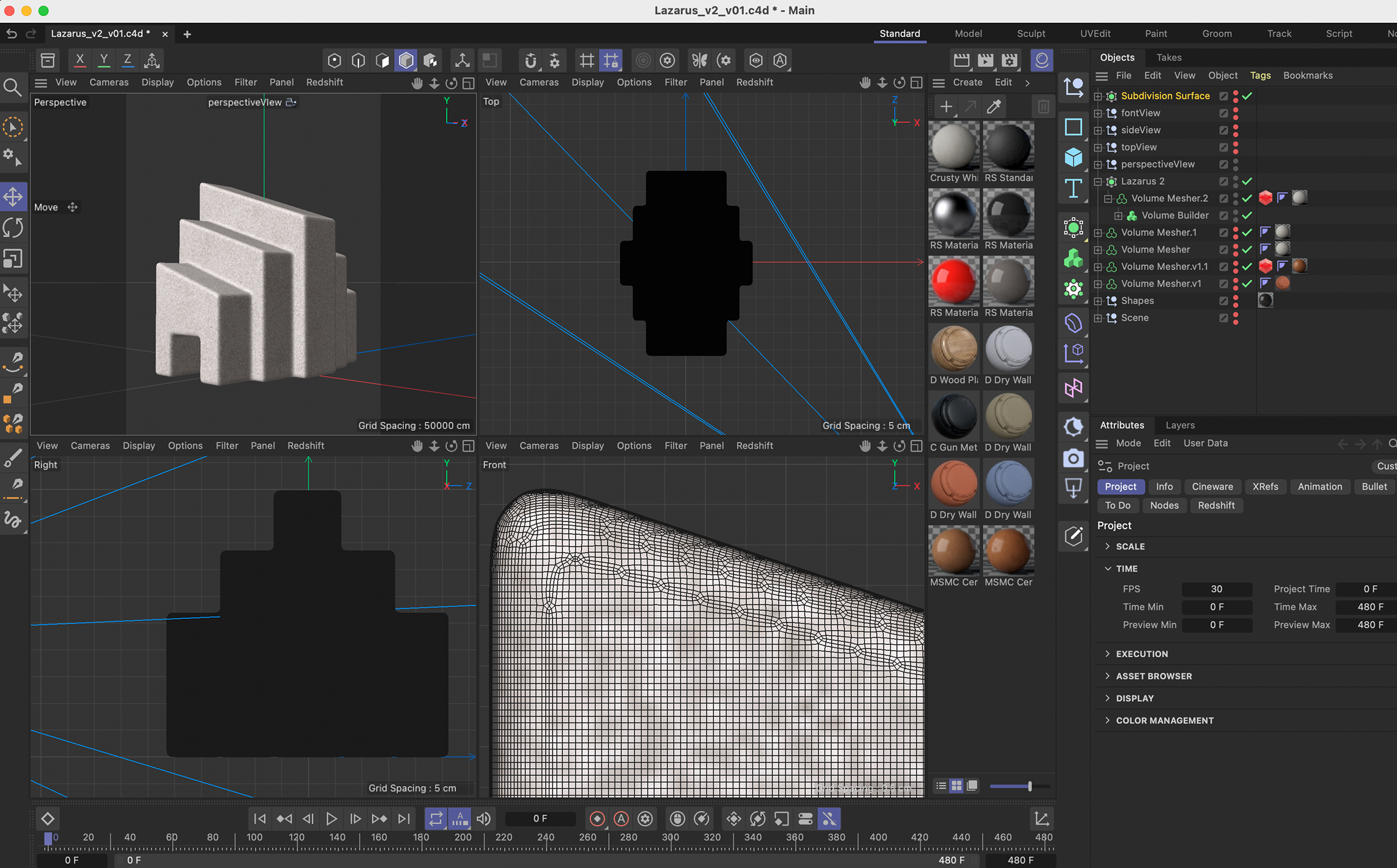

Sculpture production process for a variety of artworks:

3D modeling (image), 3D printing, sanding and prepping for ceramic mold (videos), work in progress ceramic mold, finished sculpture.

I was first introduced to your animation work and later discovered your coded artwork and sculptures. Can you walk us through how you've maintained this dual practice of both traditional artmaking and motion design for major tech companies?

What does each domain give you that the other cannot, and how do they inform each other?

I was drawn to art from an early age and studied it in college in the late 90s. Around that time, someone in a class showed me a Flash animation, and I fell in love instantly. That moment changed my trajectory. I became fascinated with making animations that could give a viewer a feeling. Using Flash and later After Effects became the tools I used first for artistic experiments and eventually for paid client work.

It began with small design shops during the dot-com boom, then led to well-established motion design studios and later to tech companies. It all unfolded very organically. In many ways, I feel like I did not choose this path, it chose me, and for that I am grateful.

Although I use very similar tools, each domain feeds me differently. Client work means solving problems alongside large teams, coming up with solutions that, if we do it right, impact millions of users. My art practice is the opposite: it allows me to go deeper into questions of memory, identity, and what it means to be human in this time and place.

Here I am not looking for answers, but for dialogue, for works that create space for questions to live. Making art is a fortunate necessity for me. I have always felt the need to make things in order to understand my place in the world and my surroundings.

Your work often explores geometric patterns and systematic approaches, from algorithmic serigraphs to 3D printed sculptures. How did you develop this appetite for coded operations and systematic repetition?

This way of working feels natural to me. My grandfather was a mathematician, my grandmother a math teacher, so I grew up surrounded by logical minds. If you have ever met a mathematician, you know they think like artists.

The overlap between math and art is strong. That background shaped my appetite for coded or systematic repetition, but I approach it with an open mind, always leaving lots of space for unexpected visual outcomes.

You seem inspired by the creative possibilities that come from setting up rules or systems, which can later create unexpected results. Is that a fair way to describe it?

I’m interested in asking myself questions and creating boundaries. I want to define the limits of my world and the rules that shape it, but I’m not interested in being prescriptive about individual outcomes. I like the visuals to emerge from within the system itself, as if they reveal what was already there and I am just discovering it rather than making it.

The outputs that come from these algorithmic boundaries can be varied, yet they carry a shared language that I hope feels like a world I am slowly building piece by piece.

The same goes when they are made into physical objects. I leave room for discovery and chance, focusing on the rules and the process, the bigger idea of why I am making something. The visual output, whether it is a sculpture, a work on paper, or an animation, is only a gesture of that larger process.

I can also see you’re inspired by nature, and yet you tend to create forms that wouldn't otherwise exist out in the wild. What attracts you to this approach?

I don’t think of myself as inventing something entirely original. I am constantly influenced by natural forms like rocks, mountains, and movements in nature, as well as patterns in traditional South American fabrics, architecture, and the materials native to Peru.

What I do intentionally is filter those influences through my own experiences and modern digital tools, and then return them in a different form. These ideas already exist in the world, and I see myself as someone who is bringing them together in a way that feels true and honest to me.

I can only hope something new comes from that process, but I am not there yet.

Have you considered the relationship between the virtual spaces, where design your work, and the physical spaces where they ultimately end up as objects?

I always think about that relationship, and I am often surprised by how different a work feels once it leaves the computer. Outside the screen, it gains presence and visual weight that it cannot have on a screen.

My practice often lives in these dualities: memory and presence, system and intuition, ancestral influences and contemporary tools, Peru and New York, digital origins and physical realizations.

All of these parallels shape how I work, and I feel at home in the gray areas where I, or my work, do not fit neatly into a category.

Algorithmic created images, pieces of charcoal, on handmade paper.

Your recent serigraphs combined algorithmic imagery with handmade paper and materials like brick dust.

Can you describe your creative and manufacturing process? How do you move from digital concept to physical realization, and what role does location and local craftsmanship play in your work?

Since childhood I have had a recurring dream where I stand in front of an enormous rock, and its scale and presence overwhelmed me with emotion. When I began that series, I returned to that specific memory and wanted to explore forms that could carry that same presence of rock formations or large walls.

I feel comfortable creating the first steps of my work digitally, so I built a library of shapes and wrote an algorithm that could generate almost infinite variations and combinations of these shapes. I was less interested in a single image than in the idea of a system that could form almost infinite visual possibilities.

But that was only the beginning. For the work to go deeper, I wanted to ground it in materials and place. I reached out to artisans in Peru who make handmade paper and was introduced to a small printer in Cuzco. I began gathering materials from the surrounding area: salt from the mines, charcoal from fires, brick dust from local kilns, soil from the farms, and small rocks from the land. These fragments became part of the work itself.

In my process, all of these decisions matter. The presence of local craft and material gives meaning to the smallest details, and in turn strengthens the larger ideas I want to explore.

A close-up of Carlo’s serigraphs showing their texture and depth.

It’s clear that you've seen firsthand how new technologies can reshape possibilities for all of us in the arts. As for AI tools, have you thought about how they might change the artist's toolkit?

We should all use AI tools to get our work done more efficiently. But I have not yet found a way to incorporate them into making artwork. I have tried, but I did not like the results, and I will go as far as to say that I have not seen any artwork made only with AI that had a strong presence or that I truly liked. I am sure that day will come, and I look forward to that moment. In my own artistic practice, it is not an obvious tool, so I prefer to keep experimenting with it in a very casual way.

In a corporate setting, however, using it has made much more sense. I use AI tools to stay productive, but lately I always ask myself a question: is this filler work or high-impact work? If it is a repetitive task with little brand importance, then I use AI as part of the process. But when it is a moment or an opportunity that could influence teams, set a tone for other work, or create something unique for the brand, I avoid AI.

Being in the tech world, it is very clear to me that these models are trained on existing work, and I find it important to go through my own process of trial and error if part of the task involves discovering something new.

When you look at your own practice, what aspects of your creative process do you consider most human, regardless of how sophisticated AI becomes?

I spend a lot of time asking myself why I am making something, what memory or tension it carries, what it means to me, and where and when I am going to make it. No matter how sophisticated AI becomes, or any tool for that matter, it cannot replace the lived experience that drives the decisions I make. It is that mix of intuition, memory, intimacy, and emotion that shapes the work.

I am reminded of a line often attributed to Salvador Dalí, in an interview where he was asked if photography would kill painting. He replied to the effect that if Velázquez copied a photograph, it would still be a Velázquez; if Dalí copied a photograph, it would still be a Dalí; and if a third-rate painter copied a photograph, it would still be a third-rate painting.

AI is increasingly mediating how audiences discover and interact with art, whether from recommendation algorithms to AI-generated descriptions. How do you think this mediation might change the relationship between artists and their audiences? Are there ways you hope to preserve or enhance human connection in your work?

I know that algorithms shape how work is seen, but that motivation doesn’t work on me. I would rather spend my time thinking, being quiet, reading, talking to someone I love, or feeling bored. Those are the moments that truly feed me and eventually go into my work. In all honesty, I make the work for myself, and if, in the process, someone connects with it, it is a beautiful gift, but it is not my goal.

Maybe one day I will spend some time coding an AI agent to act as my PR robot. That way I can focus on the work itself while it worries about the views.

While I have experimented with a lot of different creative tools in my career, I’ve noticed that very few have felt like a natural extension of my own instincts and impulses.

With the emergence of so many new ones lately, I wonder how you approach new tools altogether. Do you see them as creative partners, as instruments to master, or something else entirely?

I love discovering new tools and tinkering with them. At first, I don’t even like to watch tutorials. I prefer to push all the buttons and see what happens as a way of orienting myself. I miss having more time to do that, and there are so many digital creative tools I would still like to try.

In the end, though, I see them simply as tools. Although I have some favorites, at the core I am tool-agnostic and choose whichever one helps me bring an idea to life in the most efficient way.

Do you have a way for deciding when a technology is worth integrating into your practice?

Two things play a big part here. At the start of projects, I tend to just try things. If I want to try it, I do it, and I make a few works to see if it sticks and feels honest. For this part of my process, I often think about the saying, “you have more to lose by indecision than by wrong decision.” I remind myself of that whenever I start to overthink. I have tried many things I did not continue, and that is fine. Failure is part of the process.

But when, in this exploratory phase, I feel an obvious connection to the larger dialogue in my work, that is when I commit. When I find a project I believe in, I begin to think about its questions much more deeply. The work starts to make more sense, and I am comfortable spending years exploring those questions and creating work inside the visual boundaries I have set.

What role do you see artists playing in shaping that future?

If one is lucky enough to be a creative soul, then living, being present, falling in love, getting your heart broken, struggling, winning, traveling, having meaningful conversations, and spending time with people you love and who love you — all of that will shape the work you create, whatever your practice may be.

Then you spend time in your craft and repeat it, over and over, until you start questioning why and doubting it all.

That cycle of living, making, and questioning is, to me, what allows beauty to be created. In the bigger picture, the tools you used become irrelevant.

Comments

Links